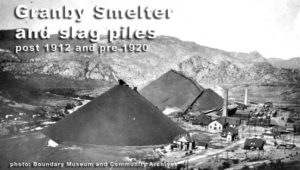

One of the unique visual features of Grand Forks is the huge black piles of sand just north of town along the bank of the Granby River (once known as the North Fork of the Kettle River). Ever gazed at those slag piles and wonder why? And when? (click on any of the pictures for larger version)

One of the unique visual features of Grand Forks is the huge black piles of sand just north of town along the bank of the Granby River (once known as the North Fork of the Kettle River). Ever gazed at those slag piles and wonder why? And when? (click on any of the pictures for larger version)

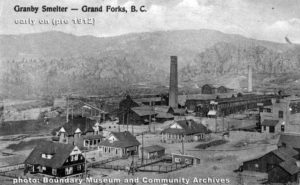

Quite a few small towns in BC had smelters and a feature all smelters left behind was slag piles. Most slag piles are large, man-made, cliffs of hard, black, rock. And down underneath all that black sand the Grand Forks slag pile is no different. But at some point in the life of the Grand Forks smelter something changed and all the slag produced from that point on was black, granular, sand.

In our running republication of the newspapers of 106 years ago we’ve caught up to that point. The announcement is in the Nov 25, 1911 edition of the Gazette.

In our running republication of the newspapers of 106 years ago we’ve caught up to that point. The announcement is in the Nov 25, 1911 edition of the Gazette.

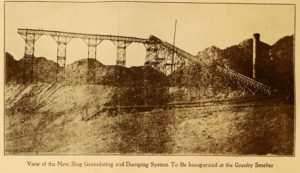

In the summer of 1911 both the Granby Smelter and Phoenix mining operations were temporarily stopped. On the front page of the November 25, 1911 Gazette the headline reads: Granby Smelter Will Blow In About December 20. There’s also a picture and description of the new slag dumping system.

It’s a story of change and progress albeit in industrial processes.

Here is how it used to work . . . (as far as I know at this point – this description cold change as we find out more details about the process actually used in the Granby Smelter)

The Granby smelter had 6 large furnaces which was where the metal was separated from the ore. This happened by mixing 3 things in the pot: Metal bearing ore, fuel (coal) and flux. The whole thing was heated to the melting point of the rock ore. The flux helped separate the metal (copper in this case) from the melted rock and that floated on the surface as a froth. (you can see an example of the ‘blister copper’ at the Boundary Museum) After the metal was removed what was left was molten slag – not all that different from volcano created glass. The large slag pot was put on rails and dragged out and up onto the slag heap. At the top it was tipped over and the liquid slag poured out. The empty pot then went back into the smelter building to be refilled and reheated. All the time it was outside the building and away from the heat it was cooling off so a certain amount of fuel and time was needed to get it hot enough to melt the mixture again.

The Granby smelter had 6 large furnaces which was where the metal was separated from the ore. This happened by mixing 3 things in the pot: Metal bearing ore, fuel (coal) and flux. The whole thing was heated to the melting point of the rock ore. The flux helped separate the metal (copper in this case) from the melted rock and that floated on the surface as a froth. (you can see an example of the ‘blister copper’ at the Boundary Museum) After the metal was removed what was left was molten slag – not all that different from volcano created glass. The large slag pot was put on rails and dragged out and up onto the slag heap. At the top it was tipped over and the liquid slag poured out. The empty pot then went back into the smelter building to be refilled and reheated. All the time it was outside the building and away from the heat it was cooling off so a certain amount of fuel and time was needed to get it hot enough to melt the mixture again.

At some point someone had a bright idea to speed up the process and save on fuel costs at the same time. This is how that went . . .

The new way of doing things departed from the old way at the point when the metal has just been removed.

Instead of moving the whole pot outside they poured the slag out and down a concrete chute. As the liquid slag moved down the chute it was hit with cold water. This caused it to solidify into granules of rock which poured into bins. These granules eventually ended up on a conveyor belt which took them out of the building and up to the top of the heap where it spilled out onto the growing mound.

This meant the melting pot didn’t have to move away from where it sat and the time between removing the metal and beginning a new pot of ore/coal/flux mixture was greatly reduced.

The savings in time also meant the pot didn’t cool off anywhere near as much which meant they didn’t have to use up as much fuel to get it heated to the correct temperature once again. This quicker turn around brought production numbers up.

Time saved, money saved and increased production.

Over time more slag sand was produced and the conveyor got longer and longer. In the picture on the right you can see a number of stretches of extension and the new piles that generated. Each extension moved away and, after a small dip, climbed upward from the last peak so each new pile peaked a little higher and spread a little wider.

Over time more slag sand was produced and the conveyor got longer and longer. In the picture on the right you can see a number of stretches of extension and the new piles that generated. Each extension moved away and, after a small dip, climbed upward from the last peak so each new pile peaked a little higher and spread a little wider.

The benefits didn’t stop in 1912 – we still reap those now in the 21st century.

Slag is molten rock. Depending on the material that was in the rock it may or may not contain toxic substances to some fraction. If the slag doesn’t have toxic materials then there might be a use for it. We in Grand Forks reap the benefits of being able to sell our slag for use in the abrasives industries. If it wasn’t already granules it would have to be mined and broken down (milled) into granular form. That would significantly add to the cost.

Not all slag piles are near to highways or railways and that would add to the cost but ours is right next to a highway and in a valley with rail service. As a result it can be sold and the revenue coming from that goes into the city’s coffers. That helps the city and all who live within it.

So the big ‘black sand’ piles began in the new year of 1912 and are still generating revenue for us 106 years later on.

You can read about this and more in the newspapers on our Old Newspapers page.

Leave a Reply